This is the GEEK-OUT EDITION. For the shorter, snack-sized version, click here. Words that are a different color (like the link in the previous sentence) are links to source articles and information. To see all the Harvest Moon Ball essays, please visit Swungover’s HMB page.

This is the first in a series that will explore the Harvest Moon Ball over the years. It is long, but that is because it is not just the story of a contest, it’s a story of a crucial year in the life of Lindy Hop. It is a story of context. It is a story full of mystery, intrigue, social disruption, mistaken memories, rediscovered truths, and an awful lot of geeking out about Lindy Hop. Hope you enjoy.

Riots and Dances

On July 7th, 1935, the New York Daily News announced it would hold an amateur ballroom dance contest. Preliminaries would be held at several locations around the city, with the final 100 couples having a full night of contests in Central Park. They named it the Harvest Moon Ball.

There is a legend that the Harvest Moon Ball was part of a public response to the 1935 Harlem Riot that had taken place a few months before. To understand what that means, let’s go to a small “five and dime” store in Harlem, on March 19th, a few months before the ball was announced.

In this store, a worker from a balcony noticed a sixteen-year-old Black and Puerto Rican boy named Lino Rivera stealing a small pocketknife. They grabbed him, and while holding him, the boy bit one of the workers. One of the workers threatened to beat the boy. The owner called the cops, and they took the Lino into a back office to keep him there until the police came. Outside, a few people began to gather. When the cop got there, Lino was untouched, and the owner, perhaps sensing the tension, told the cop he wasn’t going to press charges. Per protocol, the cop called an ambulance to look after the bite. To avoid the crowd growing out front, the cop made the tragically naive decision to take the boy through the basement to exit the store out the back.

For decades, Harlem had seen what America had thought of its Black communities: The streets were potholed, the playgrounds in disrepair, their hospitals neglected, and they were red-lined into neighborhoods with terrible property values and amenities. The unemployed gathered on street corners, and Black Harlem workers were often “the last hired and the first fired” — Harlem was a mostly Black community full of white-owned businesses that only hired Whites for anything but their most menial jobs. And the Harlemites — for good reason — they didn’t trust cops. Throughout American history, law enforcement in general has notoriously used their power to oppress people of other races and cultures. And the Black American population, from the country’s founding to this very day, and tomorrow, has been an overall victim of this oppression. Harlem was no different.

When the cop walked young Lino down into the basement, a woman who was keeping an eye through the window suspected the boy was going be beaten. The ambulance pulling up made the crowd outside even more anxious. Dreading the worst, a woman fainted, and yet another ambulance was called. More anxiety. A hearse was parked across the street that day, and so people learning about the situation and coming to see for themselves drew conclusions. If it were a movie, you would think the writers were overdoing the tragic coincidences.

It didn’t help that this Harlem “five and dime” store had already made its Black community anxious before. It had been picketed months earlier for refusing to hire Black employees. A Harlem communist organization with both White and Black members, called the Young Liberators, now heard the rumors about the beating of a boy of Color at the store. They quickly made signs and printed bills claiming the owner and the cops had beaten the boy, and the woman who rose to his defense. They demanded the release of the boy and the arrest of the owner — note it was a call for protest, not a call for blood. A crowd grew around them as they peppered the community with the printed bills. In response, the police tried to produce the boy who had been sent on his way, but the address had been misunderstood, and they scrambled to hunt him down.

The crowd at the store grew into a frenzy, and the frustration and tension finally snapped. A brick flew through the store’s window, and then another, and then another. What the papers would call the Harlem Race Riot had begun; a series of small, telling misunderstandings had exploded an oppressed community into the first modern race riot, like a stray spark falling on gunpowder and kindling.

Riots are never invite-only, and soon the concerned and frustrated protesters were joined by looters and those wanting to hurt somebody. Some of the police took to beating community members simply making protests speeches, and some of the rioters took to beating police. Owners of Black-owned and Asian-owned businesses put up signs saying they were “colored stores,” hoping to avoid the wrath of the riot. Properties all over the neighborhood were damaged or destroyed, and The Savoy Ballroom took enough damage that it would have to close down for repairs. The riots didn’t just involve People of Color; just as a few handful of groups of People of Color went around beating up Whites, a handful of groups of White people went around beating up People of Color. Whites appeared in the arrest reports for looting and assault next to People of Color. Someone took the opportunity to shoot someone and got away without discovery, the first death of the riot. One of the Daily News own photographers had to go to the hospital for lacerations to the head.

And then — symbolically, tragically — the horrifying deja vu Black America experiences over and over and over again — a policeman shot and killed a 15-year-old Black boy who ran away when the officer told him to “halt.” The boy’s name was Lloyd Dobbs.

It would be around two in the morning before the police could finally track down Lino and prove he was alive and untouched, at which point the unrest was too far gone to stop. The boy had fallen asleep in his home and had no idea the riots were going on. Ultimately, 4000 people were thought to be involved in the riot (less than one percent of Harlem’s population). And at least four people, all Black, died in its wake.

Despite the violence that did happen, the riot was known as the first race-based riot where people in general took their frustration out on property rather than physically fighting people of other races.

At the hearing, when the leader of the Young Liberators was asked why the group had assumed there had been a beating without any proof, he said because so many similar occurrences had happened before, they saw no reason to doubt it. Let that remind us all — the riot’s origin in misunderstandings is a red herring that can take our attention away from the fact that the resulting explosion of frustration was inevitable. It could have just as easily happened after an actual beating, at which point there would have been yet one more victim of it.

How does the Harvest Moon Ball play a role in all of this? The legend goes that, following the riot, the Mayor worked in conjunction with the Daily News to put on a dance contest to raise the spirits of the city and show unity. We’ll examine that more in a moment, but first, here are some things we definitely know happened after the riot.

After the riot, Mayor LaGuardia put together a group of experts and community members both Black and White to report on the causes of the riot. The exhaustive study would take a year to complete. When it was released, it was hundreds of pages that touched upon every corner of Black Harlem life.

Perhaps to the surprise of the government, and the anger of law enforcement, the committee found no one person or group responsible, but instead blamed “injustices of discrimination in employment, the aggressions of the police, and the racial segregation” of the city as the culprit. Perhaps further surprising and angering the respective bodies, it did not condemn — but instead praised — the Harlem communist organizations for helping build good relationships between Whites and Blacks in the neighborhood in general.

To his credit, the mayor took some action. (And to his discredit, not that much, ultimately, and also never officially issued the report to the public, presumably to cover up the alarming results of the study). But Harlem got some new schools and a new health center, and the mayor hired Black American judges and staff members to help him keep his finger on the pulse of the Black community. But in reality little changed for Harlem — another, bigger, more deadly riot would happen before a decade would pass.

The Harlem Riot is considered by many to be the symbolic end of the Harlem Renaissance. To us swing dancers, it’s interesting that a time of such potent Black American artistic and intellectual flourishing would come to a close just at the time America’s own folk dance — created in the heart of the Harlem Renaissance — and the music it was danced to — the swing music that evolved greatly in Harlem — would suddenly begin to flourish. In our art forms, at least, the renaissance seemed to just be beginning.

When the Harvest Moon Ball was first announced on July 7th of 1935, they announced four categories: Tango, Waltz, Fox Trot, and Rhumba. Lindy Hop was not part of the original plan. Then, an interesting thing appeared in the paper on Wednesday, July 10: A reminder of the contest, with the same four dances. It lists the locations of the prelims, of which the Savoy Ballroom is one. And above it, they placed a picture of Lindy Hoppers at the Savoy.

First off, notice the inherent racism of the caption. Unfortunately, the Daily News often links Black Americans to “instinctive rhythm” in this era, as we will see. Maybe Lindy Hop wasn’t considered for the contest because the organizers were only thinking of the mainstream popular “Ballroom” dances for their competition. But this caption might also provide a hint at why none of the popular ballroom dances included any Black American ballroom dances. The institutionalized oppression that fueled the Harlem Riots is still here, even in this caption.

Then, on July 13, “with the cooperation of the Park department,” they announced the Lindy Hop would be added to the contest. You might be asking what role the Park Department had in deciding whether or not Lindy Hop was added to a newspaper’s dance contest. The answer was revealed the next day when the paper explained the addition. Turns out, Harlem’s Colonial Park had held an outside Lindy Hop dance in the park Thursday (July 11th), and one of the park administrators thought it would be perfect for the event. Here’s what the explanation article said:

You never know what small action will lead to changing the world. Had James, a supervisor for a parks department, not gotten in contact with the Daily News, there might not have been Lindy Hop in the Harvest Moon Ball. And then, as we’ll discover, Lindy Hop’s future might have looked very different.

If we take this Sunday article at face value — despite the suspicious picture of Lindy Hop next to the Non-Lindy Harvest Moon Ball announcement the day before this Thursday park party — it means at most two days had passed for them to make this decision after the park dance, and work out the details with the Savoy. Let’s look to Norma Miller for how that might have gone down. In her book, she talks about a meeting between two people from the Daily News and the Savoy’s manager Charlie Buchanan, and Herbert White, who was seen as “the prime motivation behind the dancing seen at the ballroom.” Her book does imply this meeting took place before the overall contest was announced, but that looks like that might have been an error, or that the meeting’s matter did not come to a conclusion until another date, at least, since the Lindy was added later. She also implied that the addition of the Lindy Hop to the contest was part of raising the morale of the neighborhood after the Harlem riots, which it certainly could have been — if not spoken outright, it would be completely understandable if it were part of the unspoken reasoning while they discussed whether or not to be part of it.

The story that the Harvest Moon Ball itself was ever created by the mayor working with the paper explicitly as a response to the Harlem riots is not mentioned once in the articles we found. All the Daily News ever said about its origin is that its “Women’s Editor,” Mary King, had the idea to put on a dance contest. And as much as the average 1930s citizen might have enjoyed dancing, uptown Harlem did not need a midtown ballroom dance contest put on in the spirit of harmony to heal its injuries — it needed access to better jobs, roads, hospitals, schools, playgrounds, and, as always, better treatment by law enforcement.

But, even if the creation of the Harvest Moon Ball and its addition of Lindy Hop was separate to the 1935 Harlem riots, it’s still very important for the dance’s history to remember that both happened near each other in time and space. And the latter certainly affected what would happen in the former — you don’t have a giant dance contest that first didn’t — and then did — feature a dance created by Black Americans from the neighborhood uptown that a race riot had just taken place in, and not have there be some underlying currents of racial energy and tension. (It’s surely one reason Norma tied them together in her book. And, it’s why we’ve spent so much time discussing the riot ourselves.)

So, Whitey, who had been coaching young Lindy Hoppers at the Savoy for years, suddenly had the biggest Lindy Hop contest in the world to prepare for. According to Norma, he was concerned about the rules. The contest had an overall winner for those who competed in multiple contests…Even though the young Savoy Lindy Hoppers did a little bit of all the basic ballroom dances, they were specialists, they weren’t likely to get far in anything but Lindy Hop. Whitey was also concerned about the judging of the contest, and understandably so — the Lindy Hop is a dance rooted in Black American artistic tradition and values, and he was hesitant to have it judged by White ballroom experts. According to Leon James, Whitey figured they would not win because they were Black, but figured they could get some gigs out of it. (Thanks, Yehoodi!)

There was one rule, however, he was probably very happy about: No professionals allowed. The Harvest Moon Ball was proudly an amateur contest. It just so happened, only a few of these young Savoy Lindy Hoppers had ever done a gig before, and all of them had some other form of job or occupation. And this meant that the dancers of “Shorty” George Snowden’s professional performance Lindy Hop troupe would not be allowed to enter the contest.

This is speculation on our part, it’s not mentioned anywhere, but the savvy Whitey surely had to see that this dance event was going to be a great chance for the promotion of his young dancers, and not having Shorty’s dancers be able to do it would allow his to take all the spotlight. (If this thought did cross his mind, it would be ironic that in the future, Whitey would arguably convince his own professional dancers to break the “no professionals” rule as early as the next year’s contest.) Anyway, Whitey agreed to the contest, and possibly made sure the Savoy prelim judges were to his liking, as we will see. The fact that the Harvest Moon Ball finals would also have the great Black swing band Fletcher Hendserson play the music for the Lindy Hop finals may have also helped ease his mind. (The band had had a residency at the midtown Roseland Ballroom for years, which makes us believe it was the Roseland ballroom that perhaps influenced that hiring. They helped the paper run the contest, which somehow wasn’t seen as a conflict of interest. More of that to come.)

At Whitey’s command, the Savoy’s up-and-coming kids were going to practice rigorously every day; he was not going to waste this opportunity. And, as we will see, those dancers will not just dance on the stage at the Harvest Moon Ball, but will use it as jumping off point for Lindy Hop, and its future.

Prelims

Overall, around 2,750 dancers competed across the five categories and seven nights of prelims. The final night — Friday night, Aug 9th — was at the Savoy. The Lindy Hop, born and bred in Harlem, was the finale. According to Frankie, this was the first contest at the Savoy that you had to register for, that had a set amount of dancing time, and which was not judged by the audience. Even though the Savoy was their home, they were in unfamiliar territory.

When the band started playing, Norma remembered it this way: “It was every man for himself. The loud yell from the the dancers meant it was on. They made noises similar to those of martial arts, the sound that releases pent-up energy.”

Frankie Manning was one of those dancers. He remembered having a lot of energy at the beginning of the two minutes, but then finding himself very tired at the end of that “Lo-oo-on-g time,” implying that the Savoy Lindy Hop contests were significantly shorter spotlights.

Frankie Manning was one of those dancers. He remembered having a lot of energy at the beginning of the two minutes, but then finding himself very tired at the end of that “Lo-oo-on-g time,” implying that the Savoy Lindy Hop contests were significantly shorter spotlights.

The Daily News put it this way:

The Harlem contest, which packed the huge Savoy ballroom on Lenox Ave and 140th St. to the rafters, was featured by the Lindy Hop, the dance which combines a mixture of all that is weird and peppy. Thirty couples, most of them colored, danced the Lindy with a relish, giving themselves up completely to the tunes of Teddy Hill’s orchestra and showed conclusively that the dance not only originated in Harlem, but is highly perfected there.

“The judges couldn’t pick one team over another,” Norma remembered, “so they chose us all. I guess they wanted to be sure and get out of Harlem without any trouble — if you know what I mean.” Norma’s great joke aside, many of the judges were connected to Harlem: There was a Cotton Club producer, a Harlem dancing teacher, a Harlem stage performer, a radio singer, an Army captain, and a prominent Harlem lawyer. (However, it was not mention how many, if any, were People of Color.) Oh, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, one of the greatest tap dancers of all time, judged.

But they did indeed choose six of the couples to move on. Leon James and Edith Mathews, Norma Miller and Billy Hill, Frankie Manning and Maggie McMillan, Snookie Beasley and Mildred Cruse, Lillian Travers and Charles Tynes, and Anna Logan and her brother George Logan were chosen to go. We know them as our pioneering dancers and our art form’s elders, but the paper’s announcement reminds us dancing was not their lives (yet): Leon was a superintendent, Edith a maid, Mildred a student, Charles a painter, Frankie a furrier. (Also, isn’t it weird that the paper TOTALLY PUBLISHED PEOPLE’S ADDRESSES NEXT TO THEIR NAMES. Who thought that was a good idea? Why was it the normal practice FOR DECADES?)

After the prelims, Whitey gave Leon and Edith, and Frankie and Maggie, his attention —according to Norma, Leon and Frankie were his prized dancers. Leon was a little older than Frankie and we get the impression from Frankie that Leon’s dancing was kind of between the older and the younger generations of Lindy Hoppers. For Leon’s part, we don’t know what he thought of Frankie, but Leon had been around for awhile and close to Whitey and it wouldn’t be surprising if he thought of Frankie as the new, young ambitious kid. Anyway, Whitey noticed Frankie’s potential and took him under his other wing.

To prepare for the finals, Frankie changed the way he was training. He began dancing full out to long songs to build up his endurance, selecting the most eye-catching material to refine, and trying to project more, which was an exhausting process for him. And he was also juggling another change to his dancing — he was told the rules for all the other dances would apply to the Lindy Hoppers. He mentions you weren’t allowed to separate from your partner, or jump, for instance. As you can imagine, this was not quite the spirit of Lindy Hop, but he wanted to do what he could to help win the contest for the Savoy.

Roseland Ballroom in midtown was a stomping ground for many of the great White Lindy Hoppers. A few days after the prelims, the Savoy kids took a trip down to the Roseland, where they were planning to see the great Fletcher Henderson perform, and scope out the competition. When they got there, the doorman said they couldn’t go in. They got upset wondering why, but the doorman still refused — it was one of those things. Meaning, the Roseland ballroom was segregated. They would have a Black band play there, but they would not allow Black clientele. The Lindy Hoppers went back to the Savoy, where any color of person was welcome. The same energy that fueled the Harlem riots was still very much surging through the city. But there’s more.

The night before the Savoy finals, Roseland ballroom had finished its own finals. Here, just so you get an idea of the 1930s news-writer’s view of Lindy Hop, is how the same reporter as the Savoy prelims described Roseland’s Lindy night:

And at the All-White Roseland Ballroom, TEN couples were moved on to the finals.

In matters of appropriation, there are often complex examples that take a lot of exploration and consideration to navigate. This is not one of them. The Roseland held swing dances and regular Lindy Hop contests — a Black American art form invented up the street, done to a Black American music art form. And yet Black dancers could not enter the place to take part. Furthermore, ten White couples were automatically going to make it into the finals, whereas there was no amount of Black dancers that were guaranteed to make it. It’s a perfect example of blatant, structural racial appropriation.

The finals were scheduled for August 15, six days after the Savoy prelims, in a band performance area along the Central Park Mall; a long, wide, elm-lined pathway crossing the otherwise naturalistic park. In fact, it was set up in the exact same place the outdoor dance of Frankie95 would take place almost 74 years later.

Before the event, all the contestants had dinner, and Norma sat with the twelve Black couples of the Savoy among the otherwise White dancers in the crowd of 164 dancers. That night, however, 100,000 people swarmed the park for the free event, that had only prepared for at most 25,000. The dancers, all on buses, couldn’t get in. The event was postponed for another date, and the contestants and audience went home disappointed. Norma Miller (still a teenager, remember) went to summer camp. She expected not to compete in the finals, and didn’t hear from Whitey. Then one day she saw her friends gathered around a newspaper article:

After reading it, she realized if they were mentioning her by name in the paper, she had a good chance in the competition. She booked a trip back to Manhattan.

When she walked back into the Savoy ballroom, Whitey explained that he wasn’t ignoring her, he just never worried about her as far as her dancing was concerned. It, and a dozen other anecdotes from her book, reinforce how hard-working and dependable she was at a young age.

On the day of the finals, Whitey gathered them at the ballroom and brought them into a huddle. Norma remembers him saying, “Tonight, you’re going up against real competition. You’ve got to show them what the Lindy Hop is all about. That we are the champs. You have got to bring back that championship. You are the flag bearers of the Savoy…Go out there and let them know who we are. You dig?”

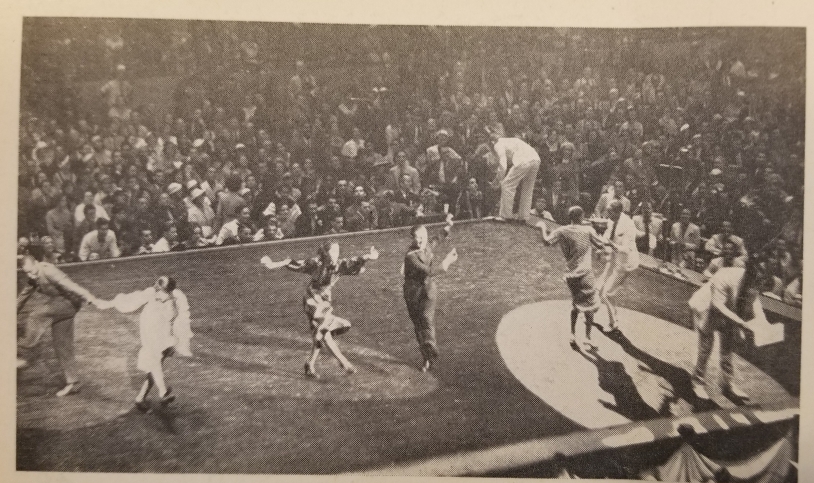

That night, Wednesday, August 28th, she and the other Savoy Lindy Hoppers were standing beside the stage of a packed, screaming Madison Square Garden. It seated 18,000, and outside an estimated 25,000 more people filled the streets when the Fire Department ordered the doors closed. In the audience, Fred Astaire, Eleanor Powell, heavyweight boxer Jack Dempsey, and Mayor LeGuardia watched. Above them, colorful bunting swagged the auditorium. A yellow moon hung from the ceiling. The stage — a large, 30′ by 40′ raised platform in the middle of the stadium — reminded one reporter of a prize fight. A prize fight without ropes.

They watched first the Fox Trot, then the Waltz, Rhumba and Tango contests. Then, the Lindy competition was announced. “The yell from the crowd,” Norma said, “could be heard all the way back to Harlem.”

The Finals

They strutted, swaggered, and goofed to the stage. They weren’t the kings and queens, Frankie said — they were the jesters. And thankfully at least one newsreel of the event still exist.

There is only one 1935 Harvest Moon Ball newsreel we know of. Let’s watch it:

This is the first glimpse of the second generation of great Lindy Hoppers. And what an introduction. Imagine dancing Lindy Hop surrounded by 18,000 screaming fans that are all there to watch you dance. If this is the original audio, notice how much it drowns out the band.

This is what Lindy Hop looked like right before the introduction of air steps. Notice that doesn’t mean Lindy Hop was without tricks. There’s plenty of powerful, dramatic, and eye-catching choices being made. If you look at couples’ Charleston and Lindy contests in the late 20s, you’ll see that even at the dance’s beginning they had plenty of the same. This performative nature of Lindy Hop is not really that — performative, we mean — it’s more akin to sharing, which goes back to the dance’s West African dance heritage, wherein most cultures’ dancing was an act not simply performed, but shared with its community in “the circle,” the great elder of the “Jam circle.”

Also perhaps contrary to your image of Savoy Lindy Hoppers, the leaders stand up straighter here compared to the “running” style that will become popular among the group in the next few years. It’s possible that styling — which Frankie describes inventing in his book — had not begun happening yet. (Though we only see a little of these dancers’ dancing in this footage. We will see the story of this trait unfold over the next few years of HMBs.) In this, there’s one small exception — Leon James does a “mule-kick” at the end of one of his turns — a brief moment of that running shape in otherwise straighter dancing.

One classic Lindy Hop trait you do see, however, is the follower’s swivel. We’ll dive into that more soon, but first, let’s see if we can put some names to the faces we’re seeing.

The Breakdown

We are fortunate, because if you didn’t realize it, the newsreel captured and gave some relatively good screen time to three of Lindy Hop’s most-lauded pioneers: Leon James, Norma Miller, and Frankie Manning. (Though it probably focused on them because even the camera operators and editors knew they were obviously worth watching.) It also shows some unknown heroes of the Savoy ballroom, dancers you may not have heard the names of, or if you have, might not have seen them dance before. To help out, we have created a version of the newsreel to help identify those dancers as best we can.

How did we do that? Well, first off, general facial and dancing recognition combined are fantastic when we can get them. And it’s only recently that the stock footage websites have been uploading high quality versions of these newsreels. Just look at some of the older Harvest Moon Ball clips on YouTube — you’re sometimes seeing digitized copies of many-times-dubbed- VCR-tapes of footage filmed by a late 90s hand camcorder possibly-illegally taken into a film archive viewing room (no judgement here, *cough*). It’s almost impossible to recognize faces in those. Now, however, those who know Frankie’s face and dancing well can clearly see his relaxed grin and characteristic head sway in this cleaner copy of the newsreel.

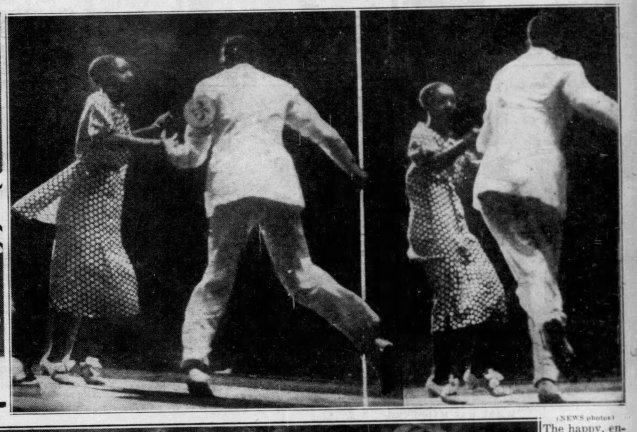

And, then, occasionally we get very lucky and find a picture of them the night of the contest:

This picture was found by searching the Getty images archives. In Frankie and Norma’s book, they both talk about how Leon and Edith won first place. So we knew Leon danced with Edith. Then we found this picture. The dress and matching jacket Edith is wearing stands out clearly in the higher-res footage, and allowed us to confidently spot Leon and Edith throughout the clip.

But, how can we be sure on those cases where there’s only a split second of them dancing, or they aren’t doing anything obviously distinguishing, and we don’t have a picture of them? How would we even have a shot at knowing who it is dancing? In these cases, what would be great is if we had something like a list of their numbers next to their names. And, if possible, in the order they were called out in.

Well, it just so happens, the day before the contest, the Daily News very handily announced the dancers and their numbers. And, as we will see, they seemed to have logically just announced each heat by going down the list of numbers they provided, so it looks like we have a basic idea of their order, as well. Why they felt it was important to give the full list of contestants and their numbers in the newspaper, we’re not quite sure, but we’ll take it. (This practice of theirs has been very helpful in putting names to faces in the footage over the years, assuming we are able to find a year’s HMB program. Though sadly we are missing many of them.)

Here’s how the Lindy Hop competition looked in 1935:

All of the Savoy finalists, with the exception of one couple, are in a group, numbers 74 to 78. (And, we were able to identify one of the other Savoy finalists, #71, by this picture.)

In her book, Norma talks about seeing the White dancers’ heats go first — they appeared clumsy to her, and made her all the more excited to throw down some real Savoy ballroom Lindy. This list shows that indeed there were several heats of All-White or mostly-White couples before the Savoy dancers’ heats.

Though, of course, number identification only works well if you can see the number. Watching the film, you might not have even noticed it, but this year the numbers were on necklaces around the Leaders’ necks — which means, in a Lindy Hop competition, they fly around, get covered by their flinging partner, and rarely stay in one place easy enough to identify them. There also seems to be something reflective about the ink, so that often we could only make out one number on a flying necklace — usually the unhelpful one.

Another difficulty is this newsreel cuts back and forth between heats so much that it’s hard to tell who was on the dance floor with whom. To make breaking down who’s who a lot easier, we spliced the dancing into the separate heats (as you will see in our breakdown clip below). Turns out, they only showed two heats.

There are four couples on the dance floor in each heat. But, if they went down the list above, that would have meant Leon James and Frankie Manning should have been in the same heat. As you will see, they are not. What most likely happened is one of the couples in the first two heats was a no-show — this would make Heat A in the clip below #72 – #75, and Heat B #76 – #79. And this seems to fit the way the heats played out. This also means all of the Savoy finalists except Anna & George Logan should be on stage in the film footage.

So, how do we know who is who? In summary: (1) Facial and dancing recognition is one way, BUT we don’t always see their faces or see them dance long enough to recognize their dancing. And many of these dancers we have never seen dance before, even though they might be mentioned in source material. (2) Frankie and Norma’s books, and other resources like newspaper articles of winners and pictures helps us know who was in it, BUT those sources can be wrong. Sometimes very wrong. (This will play a role when we discuss the 1940 Harvest Moon Ball.) (3) The list of contestants and numbers, if there is one, helps us confirm suspected dancers or learn new previously unseen dancers, BUT the numbers are often not visible, and furthermore, Frankie and Norma mention sometimes there was partner switching at the last second. And, (4) the order is how we know the rough idea of who should be in a heat, BUT as this one has already taught us, who should be in a heat is not necessarily who is in one. That’s a lot of factors in play, and when enough of them line up with some good old-fashioned gut feeling, we feel confident saying we’ve got a positive identification. But we obviously don’t always have all the pieces we need for an absolute identification, and even with gut feelings, we always have to be mindful of the numerous potential problems.

That’s why, in our breakdown clip below, if we are reasonably sure of the couple’s identification and the evidence all lines up, we list their number and names near them. Otherwise, we list a “Most likely” above their names if we are almost positive, and a “Possibly” if there is at least some reason that it could be them but we are not sure. Finally, since there’s a lot of fast action and cutting, we run the footage at 70% after we’ve run it through once at full speed, so you can take it in a little easier.

With that in mind, let’s see that footage again, and get an idea of who’s on that stage.

The 1935 Harvest Moon Ball Breakdown

All right, now let’s talk about what we’re seeing. (A collection of the original newsreel and this breakdown clip will be put on YouTube soon.) It’s worth noting that none of the White-only heats appeared in this newsreel. Which is interesting to think about.

Heat A

The obvious stars of the first heat are Edith Mathews and Leon James (#75). All of the eye-catching personality that Norma and Frankie attribute to Leon in their books is on full blast here — there’s the striking moment of him wiggling his legs, shaking his finger; there’s the arm-swinging double turn he and Edith do; and, there’s his circle-and-stop into Charleston:

While rubberlegs and some of his other audience-catching tricks are skills many modern dancers could achieve if they want it, Leon’s sense of timing and minimalism are truly masterful. In this little stop before going into Charleston (above), you see his legs cease moving and then slide with beautiful syncopation right into the energetic Charleston. He would take this skill to incredible heights, as seen in one of his dances in the jam circle in The Spirit Moves:

Edith Mathews has a very special place in Lindy Hop history — according to both Frankie and Norma’s books, she introduced the follower’s swivel motion into the dance. The story goes that she and “Twistmouth” George Ganaway, one of the great first generation of Savoy Lindy Hoppers, showed them to Whitey while Frankie was there. Frankie learned them first by stealing them, but then ended up simply asking Edith to show all the other dancers. We don’t see her demonstrating swivels here, which is too bad. According to Norma, “she had a sit-down twist that made her whole body look like a pretzel.” However, we can tell they were really popular at the time, as several of the other Savoy followers turn them on full blast.

Edith and Leon match incredibly well. Norma and Frankie spend a lot of time giving Leon credit for his eye-catching dancing, but Edith is bringing plenty of it herself without question — she’s shaking her hand and her head in ways that match his “legomania” energy and finger pointing, and even though her back’s to the camera through a lot of it, her expressive body language shows she’s having a blast. From what little we can see, it looks like she balances out their partnership by adding a lot of full-body energy to contrast and yet still compliment Leon’s more minimalist movement.

Edith and Leon’s outfits were perfect choices. He must have known a white suit would pop out on that stage in that backdrop of 18,000 people. (And if New Yorkers then were like New Yorkers now, it would have been 18,000 people dressed in dark colors.) Edith’s dress and coat flowed with her movement, and the jacket flared out to take up even more space. They clearly planned their clothing to match their dancing.

Next to them are most likely Mildred Cruse and Snookie Beasely. It’s very hard to make out this couples number (other than a “7”), but Mildred and Snookie had #74, which is right next to Edith & Leon’s number. The two are the only Black couples in their heat (which you might not have realized until now — the camera only shows the White dancers in the far away shot). A still-shot of Mildred’s face looks pretty similar, and Snookie was taller, as this dancer is.

Sadly, the choice of the editor to repeat the move they do make it look like they spent half of their heat in a bent over kicking dip. So we don’t have a lot we can say about their dancing — except it is a great example of how the air steps that would soon be coming to Lindy Hop weren’t so much an addition of new energy into the dance, as much as they were a natural progression of energy already there. But check out the move where the leader simply moves backward while walking the follower forward. How beautifully simple, and yet stylish. And most-likely-Mildred’s free hand gesturing is both casual and evocative — they have made a shine move out of walking. And here she puts out her own take on the recently-popularized swivels.

Finally, before moving on, we should acknowledge that most-likely-Mildred’s outfit is really fantastic.

Let’s take just a moment to look at the other couples in this heat, two Non-Savoy Lindy Hop couples of the era. We can only see them for a brief moment, so anything we can say about them is based on a terribly small sample size, but let’s take some guesses.

First off, they are obviously good dancers. The couple in very dark clothing especially moves in a style we tend to value today — strong rhythmic kicking, charging pulse, and good flow throughout their movement. But both couples share a few characteristic traits that contrast with their Savoy dancing neighbors.

First off, even though the Savoy leaders next to them are dancing “upright” compared to how they will dance in a few years, these non-Savoy leaders are dancing even more upright. The Savoy dancers here tend to dance in a slightly more grounded posture, which we known allows them to harness more power to use in their body — it’s a trait Savoy dancers especially will develop more and more throughout the years, giving us the kind of Lindy Hop you see in Hellzapoppin. (And it’s the way almost universally taught today.) Secondly, the non-Savoy dancers don’t allow their torso or their arms to express near as much movement as their Savoy neighbors, who are constantly swinging their bodies and using their arms for naturally-swinging movement or styling. Thirdly, the non-Savoy dancers don’t have that powerful commitment to their movement their Savoy neighbors have in their kicks, swivels, and arm movements, and, well, everything. (It’s often referred to as “attack,” a term that, if taken neutrally, is an accurate description of it, but unfortunately is a term that too easily speaks to the history of linking violence to Black Americans.) It’s a huge part of the swing of the Savoy dancing, and, paradoxically, the “relaxed” look of their dancing. The couple in darker clothes is a lot closer than the other non-Savoy couple, but still the overall effect is that both of these couples’ dancing doesn’t look as present as the Savoy dancers next to them. Finally, they don’t appear to share as much of their dancing with the audience, like we mentioned earlier. Their Savoy neighbors are obviously dancing not just for themselves, but for, and with, the audience.

We mentioned earlier how sharing was a technically more correct way of describing the “performative” nature of Lindy Hop, and how that was a value handed down from its West African heritage especially. It is most likely not a coincidence that ALL of these ways of moving we have just described — grounded postures, expressive arms and torsos, commitment to movement — are values commonly found in the dancing of the peoples of West Africa, the major source of enslaved peoples that have arguably passed these elements of their culture down through the generations of Black Americans. For just one example, look at the movement in this clip of Guinean dancers doing the traditional dance Dundunba: (By the way, as a word translated from many different languages, there are often multiple accepted spellings for this dance. Other misspellings in this piece I have no excuse for.)

Here all of those key elements are on display — grounded posture, full-bodied expression, attack of movements, and sharing with those taking part. Now, this is not to say ALL Black Lindy Hoppers, or all of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, embodied all of these principles — just that they were commonly found in many of them.

And though we may critique these non-Savoy couples’ dancing, we don’t mean to criticize them. They, like most of us currently dancing in the modern scene, obviously were passionate enough about Lindy Hop to work very hard on it, and based on what we see, it seems reasonable to give them the benefit of the doubt that they are trying to accurately embody Lindy Hop values as best they could despite coming from a different culture, especially for their time and place. Something we thankfully do NOT see from them, that we will see when we dive into future Harvest Moon Ball footage, is White people doing a caricature of what they think Lindy Hop values are. Oh yes, there will be anger, cringing, and face-palming. (Oh, and, as you can imagine, there is still plenty of that going on in the modern scene, as well.)

Heat B

Frankie Manning and his partner Maggie McMillan (#78) are clearly visible in this heat. But they are mostly only seen doing the same move from two slightly different camera angles — a smooth sailor-kick Charleston move that comes in and cuts off as soon as they get into closed. It’s not a lot, but at least it’s something. We see how graceful and connected they look, we see how relaxed and casual they are. We see how clear their rhythm is, and how in sync they are with each other. We see Frankie’s tell-tale little head shake and the casual smile that stretched across his face when he danced or told stories. We see Maggie has an elegant yet easy dancing demeanor.

For her part, Norma didn’t think Frankie and Maggie were the best match — her main reasoning seems to be that Maggie was too close to him in size, probably implying that he wouldn’t be able to do some of his impressive and powerful trick dancing with her. If you gave Frankie the right partner, Norma said, he was unbeatable. Frankie, for his part, thought she was one of the best followers of the ballroom, and the five seconds we have of their dancing is beautiful — they were clearly great partners for each other in movement, and, as we have seen in their published rules, in everything the Harvest Moon claimed to value.

Let’s look at the two other Savoy couples in this heat:

Recognizing Norma‘s partner, Billy Hill, in the footage was easy, once it sunk in that his nickname was “Stompin’” Billy. Sure enough, he does a swing out where he just starts slapping a foot on the ground, as if wanting to make sure future generations knew where they could find Norma in this clip. (We still say “most likely” in their clip ID because we almost never see Norma’s face very well and Billy’s number isn’t visible enough, so we erred conservatively. But it’s almost definitely Norma.) For the record, the swing out you see them do is technically this generation’s earliest full swing out on film that we know of. And it’s the only swing out in the clip.

They aren’t on camera long, but you can see some of Norma’s powerful twists as Billy begins stomping. And, she appears to have the sort of bob hair cut similar to the one she would sport often in her older age.

Let’s take a moment to learn a little about her partner, Bill. Black Americans were, and are still, never allowed to forget they are Black. Even when they are young like these dancers. Norma mentioned in her book that Billy at this time had a White girlfriend, and in general it was making Whitey nervous. (We’ll get to specifically why later, though you’ve probably already got the gist). His girlfriend was there by the bandstand, watching him that night, cheering him on. But afterwards, they dared not go near each other in the midtown venue.

This means the third Black couple dancing in similar ways to the other Savoy dancers, is most likely Lillian Travers and Charles Tynes (#76). Their number is next to Norma and Bill’s on the list, and in the only other Savoy couple involved a White woman. (We would have put “Most likely” on their ID but had found the proof of the other couple after all that material was already created, and figured it probably didn’t hurt to err conservatively.)

They do a similar dip-and-kick move as most-likely-Snookie-and-Mildred do — it might have been popular at the time. They also do a move where the follower swivels back and forth for awhile in open position — apparently another popular move at the time since Norma, most-likely-Mildred, and likely-Lillian all do it in this clip. The styling most-likely Charles does where he lunges and points his finger and punches his arm a few times — that moment is seared on our brains. It’s just a really recognizable moment from the Harvest Moon Ball footage.

As you can see, ironically, the only Savoy follower who doesn’t spend some time carving out some swivels in the footage is Edith, their inventor.

Finally, there’s a snippet of a White couple dancing in this heat. If they followed the numbers on the list, and the heats are mapped out as they appear, and the couple showed up and danced, then the young leader there is Harry Rosenberg (#79), who was the leader in one of the small number of White couples in Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers. It’s hard to get a comparison of his face, but here is a picture of the couple from the preliminaries, and it’s probably a good bet it’s them. When he was with the Whitey’s, he would work with a partner named Ruth Reingold. They only performed with Black members of the group in a few places in New York — outside of the city, social and business pressure kept the group segregated.

Finally, there’s a snippet of a White couple dancing in this heat. If they followed the numbers on the list, and the heats are mapped out as they appear, and the couple showed up and danced, then the young leader there is Harry Rosenberg (#79), who was the leader in one of the small number of White couples in Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers. It’s hard to get a comparison of his face, but here is a picture of the couple from the preliminaries, and it’s probably a good bet it’s them. When he was with the Whitey’s, he would work with a partner named Ruth Reingold. They only performed with Black members of the group in a few places in New York — outside of the city, social and business pressure kept the group segregated.

In his book, Frankie praised Harry greatly, saying that at some point Harry could do most of the things Frankie could (by watching Frankie). According to interviews Judy Pritchett conducted, Harry himself put it in a humorous way: Harry wanted to be the best dancer in the Savoy. Soon after, he saw Frankie. Then he said he wanted to be the best White dancer in the Savoy.

In the program, the judges would make their decisions following the contest, and then the top three places would be announced. Those couples (“teams” as they often called them at this time), would then dance for the audience in a short victory exhibition.

Speaking of judges, this time they were a lot less representative of Harlem — they included the owner of New York’s Roseland Ballrooms (No conflict of interest here), the founder of the Rockettes, a producer at Radio City Music Hall, and dance school magnate Arthur Murray himself, who would go on to simplify and arguably white-wash Black American dances like Lindy Hop for teaching in his schools.

The winners, according to the paper the next day, were Edith and Leon in 1st, Rita Mullen and John Kay in 2nd (they were Roseland finalists, here’s their picture in advertising for 1936’s competition), and Maggie and Frankie in 3rd. The 2nd place Roseland couple most likely appeared in a final three-couple heat that is not shown.

We do, however, have this picture from a 1945 Dance magazine article:

This is almost certainly the winners’ exhibition, showing Maggie & Frankie on the left, Rita & John in the middle, and Esther & Leon on the right.

There are dozens of different possible reasons behind how this contests’ judging played out. Aside from their specific-perspective-driven opinions on dancing, we don’t know what other factors were weighing on their decisions. We also haven’t seen all of the couples dance, and therefore can’t make an accurate judgement ourselves. The paper did mention this as the criteria they were allegedly supposed to use:

But when it came to the Lindy Hop, some, or all of the judges, might have thrown that criteria out of the garden (as well they should have — how does one know the proper execution of something original, anyway? Especially in a dance like Lindy Hop?) Regardless, it is probably fair to look at the makeup of the final judges and be suspicious of them, as a majority, having a firm grasp and non-biased view of Lindy Hop. We’re not contesting their results, we’re just simply trying to see the situation as the Lindy Hoppers might have seen it. Remember — in Norma’s book, she mentioned Whitey being concerned about the dance being judged by people who didn’t understand it. And, he was wise, and apparently spotted the situation clearly. And in a moment, we will argue he possibly planned for it.

Now, veteran swing dancers: What if someone asked you to name the top three winners of the first ILHC strictly contest? Or, the top three spots of the first big contest you were ever in, if you were in one? Or, what if someone asked you what happened while you were in that contest, and wanted detail? I could maybe tell you the 1st place winners of my first few big contests, or an experience that stuck out in my head, but I certainly would have problems pinning down 2nd or 3rd, or telling you much more about the experience. And chances are I’d get some part of that wrong. And those are contests that have happened within the last two decades. Now imagine you are Frankie or Norma, and you are being asked to remember details about events that happened almost five or six decades ago? No matter how hard you tried, there’s bound to be fifty years of memories mingling, retold stories evolving, and fantasy fading into facts. Like beauty, history is in the eye of the beholder.

In his book, Frankie remembers dancing on stage in the same heat as Leon, and all the Lindy Hoppers moving from their spots to dance in front of the judges. For Frankie, he remembers it being hard to get in front of the judges with Leon and Edith taking up the spot so vigorously. And it does look like the Lindy Hop dancers are all comically congregating in one part of the large stage. But as you can also see, Frankie was in a different heat than Leon. Perhaps he was thinking of the other Savoy leader in his heat in a white suit, who was dancing next to him — Most-likely-Charles Tynes has a lot of dancing similarities to Leon. Or perhaps Frankie was thinking of the exhibition dance after the winners were announced. Or perhaps he was thinking of a different time when competing next to Leon. It’s the cruel paradox that our memories are not only archivists, they are also tricksters.

Also in their books, Norma and Frankie both remember the Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers taking the top three spots, but the paper announced otherwise. In the next five Harvest Moon Balls, either Frankie or Norma, or both, will take part. They will swear they were with partners they weren’t. They will swear they weren’t competing in years that they obviously were in. Memories are tricksters. But far from blaming them for recalling false memories, we must always remember the difficult thing we asked them to do — to sift through thousands of similar memories that happened more than half a century before.

“Rules”

Remember how Frankie was sweating over the rules? Leon and Edith did not. In the footage, it can be hard to see, but they broke apart from each other and danced solo Charleston side-by-side. They didn’t stay in their corner. They went out and danced the Lindy Hop the way they thought it should be danced. And won. Though Frankie doesn’t literally say it, we detect underneath the writing that he might have gotten a valuable lesson from the experience.

This is complete conjecture, but if we again remember that the Lindy Hoppers were overseen by a great strategist — as Norma put it “Whitey was the original stage mother, he left nothing to chance. Every detail was worked out in advance…” — It wouldn’t have been out of character if Whitey encouraged one of his top dancers to play by the contest’s rules, and the other to play by Lindy Hop’s rules, as a way of ensuring the best outcome.

Speaking of making one’s own rules and Whitey, there is an interesting sentence in Norma’s book: “Leon James may have won the Harvest Moon’s first prize, but Whitey held its diamond ring.” We don’t think Norma was speaking figuratively — the prize for first place was a diamond ring. The sentence, if taken at face value, means Whitey literally kept the diamond ring prizes for himself. Whitey was exactly the type of person who would see it as the price for his coaching and management. If you think this is too speculative, here’s another interesting story:

In 1939, Savoy Lindy Hopper Connie Hill won with Russell Williams. Walking to the Savoy after the contest that night, she was mugged and left unconscious. “They received nothing for their efforts,” the newspaper reported, “as White who heads the famed Lindy hoppers had carried the watch home with him.” Later in the article it says “After the contest the Hill girl turned her watch over to Whitey, owner of the team, who took it to his own home.” Interestingly, it has repeated the statement without explaining any more possible motives other than to continue to put emphasis on the fact Whitey took it to his home.

The reporter either didn’t ask for more information, or didn’t get it if they did. Regardless, it looks like they might have tried to imply the suspicious arrangement by repeating it and rewording it in the article.

Overall, Frankie wasn’t beat up about losing to Leon. He also wasn’t that excited about the contest — he thought Fletcher Henderson must have been off or something, because the music wasn’t very inspiring. (In the notes of his book, co-author Cynthia Millman said it was likely because Fletcher was having some pretty problematic personnel problems at the time. ) Frankie was just happy the Savoy dancers won top awards, and he knew that, at the Savoy, he was considered a great dancer, and that’s the only place he cared about. Frankie’s zen attitude is a hard one for some people to find. We can certainly sympathize. But imagine what it means to find that place, that place where no other opinion matters. Where your dancing confidence is only linked to the place your dancing calls home.

The Next Day

The New York Daily News had made news. The next day, its front page mostly featured the bold words of 60 deaths in a French-Ethiopian conflict. The world, obviously, doesn’t stop for a dance contest. However, the Daily News was known for its use of photographs (it boasted it was “New York’s Picture Newspaper”), and throughout the day it offered two-page photo spreads of the ball.

And though we could always do with more pictures of our Lindy Hop elders, pioneers, and heroes, they at least provided a few:

The day after that, they published photos catching up with the winners (in their homes, apparently, which is where photos shown earlier in this article were from), and they also posted a candid story on the experience of deciding to put on the ball, and that, financially, the Madison Square Garden tickets allowed them to cover the tanked costs of the Central Park debacle. The event broke even. To show you how candid the article was, they mention how they had found out only the day before, from their own weather bureau, that the Harvest Moon was in mid-September, not August.

They also announced the 1936 Harvest Moon Ball. They would still keep the name, and it would still happen in August.

The Aftermath

Following the contest, Leon and Edith performed at Loews theaters in New York for a week as part of their first prize — all the first place couples got to do the show and were paid for the contract. But arguably the biggest winner of the night was Lindy Hop in general. The dance was the hit of the night, and 18,000 people saw it and walked away and many of them talked about it to their friends. Even more importantly, it was instantly the favorite dance of the newreels, and the 1935 newsreel would introduce it to people all over the world. The Lindy Hop of the younger Savoy dancers had gone from only being seen by the tourists who made it a point to stop by the Savoy, to globally, in only the amount of time it took to create and distribute a newsreel.

Whitey immediately began getting requests for his Lindy Hoppers to perform, the biggest offer being a long tour of Europe for the winning Savoy couples. Frankie did not want to go — he had a good job as a furrier and thought that was going to be his career, and wouldn’t abandon it. Despite Whitey spending an entire night until dawn trying to talk him into it, Frankie held firm. Maggie was very upset, as Whitey would not let her go without Frankie as her partner. She would soon after cease dancing with Whitey’s teams to work for “Shorty” George Snowden’s performance group.

Norma skipped school to go on the tour, with her mother’s permission. It was a low quality school that didn’t offer her much, and, being a teenager wise beyond her years, she realized now was the prime time to start pursuing a career in dancing.

Billy also came along, and Whitey was relieved, as it got him away from his White girlfriend. Remember, Black Americans are never allowed to forget about their race for very long — and the practice of White women going to Harlem to dance and interact with Black men was noticed by a lot of downtowners. And though they couldn’t shut down the ballroom for being integrated, they could get it shut down for illegal vice. Rumors started to spread that the famously elegant Savoy hostesses were part of a ballroom prostitution ring. In reality, they were forbidden from dating customers or musicians, and Charles Buchanan was so anti-scandal he was known for having “eyes in the back of his head” and being a “slave driver” as Norma put it, to keep them on the up-and-up. They weren’t even allowed to drink in the Savoy. The rumors were most likely created to try to get the ballroom shut down. It never happened, but it was clearly an ongoing concern. Whitey had already been concerned about one of his dancers dating a White woman and the problems that could cause — now he had even more reasons.

And so Norma and the others became the first Lindy Hoppers of their generation to perform in Europe. They had a difficult time with their performances on tour. Probably surprising none of our veteran Lindy Hopper readers, the cruise ship bands and small theater orchestras of 1935’s Europe apparently — to borrow a favorite phrase of Norma, not mentioned in her book — “couldn’t swing if they were hung,” and Norma realized for the first time how truly important the music was to Lindy Hop, and how spoiled they were dancing at the Savoy every night. She also sang some numbers, while on tour, the beginning of her multi-talented stage career.

While Norma, Leon, Edith and Billy were away on tour, it just so happens that back in New York, Frankie more or less began the next Renaissance in Lindy Hop. First off, as he recalls, a few months after the Harvest Moon Ball, he took part in a contest at the Savoy that pitted Whitey’s young dancers against “Shorty” George Snowden‘s veteran Lindy Hoppers. Shorty and his partner Beatrice “Big Bea” Gay had an act they had perfected but which changed so little it had become predictable to the young dancers. In it, they had a famous exit step where she would lock arms and walk off with him on her back kicking his legs in the air. Riffing on this step, Frankie and his contest partner, Frieda Washington, made it so that Frankie not only took her onto his back, but kept her going — flipping her over. The first air step in Lindy Hop was born. Suddenly finding a whole new unexplored dimension in the dance, all of the younger dancers started making up new air steps.

But that wasn’t all — not going to Europe opened up Frankie to New York’s gig opportunities, and the constant performing inspired other new innovations. He was in the ballroom, playing with freezing to the breaks in the music, when he decided to freeze NOT on the breaks to the music, and thought it was cool. Then he invited others to do the same thing he was doing at the same time — this was not only the birth of the “stops” routine, this was also the first Lindy Hop ensemble dancing. He took it to the theater shows. It was most likely during this time that he also introduce the audience-loved “slow motion” gag.

Though dancing in Europe was a disappointment, the touring Lindy Hoppers understandably had a blast. And if you ever had the fortune of knowing Norma Miller, just imagine the young-adult version of her strutting through London and Paris without chaperone, allowed to do her own thing. She greatly enjoyed her freedom, and upon her return, she decided to light a sophisticated cigarette in front of her mom. It got snatched out of her mouth, and Norma got snatched back to her teenage reality.

The night they returned, Whitey took them to see Frankie and his group at the Apollo — after the Harvest Moon Ball, Whitey’s dancers were indeed doing well; The Apollo was one of the signs that a performance group had made it. Imagine what it was like for those recently-returned Lindy Hoppers to go away for several months — 22 weeks by one future Daily News account — and come back to see the dance they knew and loved — had known so well they had become the first world-recognized champions of it — to come back and find that dance had changed, possibly dramatically, while they were gone. Norma was amazed, but also was not going to be left behind. According to Frankie, she picked up the new ideas quickly. When it came to Leon, however, Frankie felt the tour of Europe had taken some of the spirit of the dance out of Leon. In Frankie’s opinion, the first Harvest Moon Ball champion never danced as well after the tour.

It’s a fascinating comment to make — this year’s HMB is the only footage of Leon we have before the tour. We have decades of footage of his incredibly expressive and stylish dancing from after. He danced almost up until his death in 1970 when he was in his late 50s, and we are fortunate to have so much of it on film from his tours with Marshall Stearns and the dancing he did for The Spirit Moves sessions. He was truly a gift to the dance and one of its greatest expressionists. If we allow ourselves to see things from Frankie’s opinion, that there was something of Leon’s spirit missing during these decades after, then how electric was Leon’s dancing, in Frankie’s eyes at least, before?

After this, the first Harvest Moon Ball, the young “upstarts” Whitey had begun training suddenly found themselves professionals. They would all in their way come to terms with it. Both Frankie and Norma’s books are in a lot of ways the story of an artist going from passionate Lindy lover to professional one. Leon James would spend many years of his life as a professional vernacular jazz dancer, one of the last surviving original dancers able to make a living off of it into the 1950s and 60s. Those three would all constantly break barriers of not only race and class, but also barriers put up against the Lindy Hop, which even show business has always had problems taking very seriously. Harry Rosenberg would break a few of his own small racial barriers, by becoming a Whitey’s Lindy Hopper with Ruth Reingold. And, according to Norma, Edith would soon after the contest bow out and stop Lindy Hopping.

But it was not only them, but also their Lindy Hop that had found itself professional — their youthful, energetic, creative, beautiful, powerful, spiritual, fly-by-the-seat-of-its-pants version of Lindy Hop, this new blossom opening on an ancient tree. And a great deal of that was because of a man with a vision — a man who, despite his faults, was still happily willing to use those very faults to insure his mission of taking America’s true Folk dance to its highest level, and its deserved recognition.

And, when Norma looked back at that night, the night of the first Harvest Moon Ball, she realized all of that started to fall in place after they took that stage. “The Lindy Hop competition belonged to us,” She wrote. “We entered the Garden as the Savoy Lindy Hoppers, but we left as Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers.”

Additional Notes

- It was probably Norma Miller’s book that the legend connecting the ball and the riot arose from. Norma really only claims the riot played a role in the Savoy’s decision, and, as we offered above, probably only discussed the riots so much because it was important for readers to know that was going on in Harlem life at the time.

- Leon James wearing a white suit and winning will begin a sort of “myth of the white suit.” I have heard stories from other historians that the dancers back then talked about it. It wouldn’t surprise me: The Harvest Moon Balls have many white-suited dancers, and Al Minns will win wearing one in 1938, and Thomas “Tops” Lee will do so in 1940.

- Notice there is an official walking around stage during the heats: This does not happen again in the HMB — perhaps due to the audience’s sight lines, though perhaps the energy of the Lindy Hop and the desire to not get knocked off stage have had something to do with it.

- Some other possibly mis-remembered parts in Frankie & Norma’s book: Norma remembers looking at pictures of Leon grinning “like a Cheshire cat” in the paper the day after the Savoy prelims — at least as far as the Daily News went, those pictures (like the one on him grinning above) only appeared after the finals of the contest. Frankie remembers there being five couples per heat — that’s probably a memory from his last years doing the HMB, 1939 or 1940. That’s the only years he reportedly did the contest that have five couples on the floor in a heat. Norma remembered the Savoy prelims band being Chick Webb, but according to the newspaper articles, it was Teddy Hill.

- Less we forget the impact Lindbergh, and flight in general, had on the world of the 1920s and 30s, the emcee for this first year was Swanee Taylor, an aviator. (With a fantastic name.)

- In the final article clipping shown in this essay (the one on Whitey), they mention a group of dancers (probably Shorty George’s group, it sounds like) going to work on an Eddie Canter film in Hollywood. This film was most likely “Strike Me Pink” which was filmed September-December in 1935 and released in 1936. (And someone has listed them in the full cast credits.) Upon going through it, they do not appear to be in it. Perhaps their dancing was cut from the picture.

- For those who have been to Madison Square Garden in the modern era, it has gone through several iterations. At the time of the 1935 Harvest Moon Ball, it was located at 50th St & 8th Ave., in the heart of the Broadway theater district, near Times Square. Here’s what it looked like:

- The entire night began with a grand march to the nostalgic, early 1900s tin pan alley song “Shine On, Harvest Moon.” It would have been a little haunting, in a sweet way. It was sung by many singers over the years. Here’s Ruth Etting singing it in 1931. Imagine 18,000 people humming along.

- In heat A, they seem to dance to approx 250 BPM, in the second heat, approx 220 BPM.

- As a sign of how far some things had come, Frankie Manning would hold his 85th birthday party in the final iteration of the Roseland Ballroom in 1999. They hung his dancing shoes on display there, along with other greats like Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Betty Grable.

- As a sign of how very far we still have to go, in February a Black man named Ahmaud Arbery was jogging when he was assaulted and gunned down by a former-cop and his son because, they claimed, he resembled a burglary suspect. At no point following the investigation were they put under arrest, and it took a video of the incident surfacing two months later and the pressure that created for law enforcement to move forward with new investigations and finally arrest them.

Sources

- All newspaper articles and pictures were taken from editions of the New York Daily News, with the exception of the story on the assaulted Lindy Hopper. That is from a story in the Chicago Defender, Sept 9, 1939. In searching for material, I soon realized the Daily News published lots of different editions every day, and they occasionally had different pictures in each edition. So if you were wondering why some pictures look different than in the links, that’s why. It also has made research both more fun, and take a lot longer.

- When not otherwise stated, all other information especially regarding the opinions and experiences of the original dancers taken from Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop by Frankie Manning and Cynthia Millman and Swinging at the Savoy: The Memoir of a Jazz Dancer by Norma Miller and Evette Jensen.

- Harri Heinilä, Doctor of Social Sciences at Helsinki, wrote a great, short paper “The Beginning of the Harvest Moon Ball and the Myth of the Harlem Riot in 1935 as the Reason for It.” It helped clear up some of the misinformation out there and helped me gain confidence in my conclusions.

- Thanks to fellow historian Karen Campos McCormack for the discovery of the Whitey’s dancer assault article, which helped us put together the pieces of Whitey’s possible “deal” with the dancers.

Coda

The Town Talk

Sept 9, 1935

5 responses to “The 1935 Harvest Moon Ball (GEEK OUT)”

[…] This is the SNACK-SIZED edition. For the longer, GEEK-OUT version, click here. […]

Congratulations for the article. Great!

[…] There are a lot of good dancers here, in terms of the quality of their movement and rhythm (just not a ton of personality expressed, at least compared to the Whitey’s dancers). And, in fact, a lot of them probably learned a lot by going to the Savoy, which dancers like Harry Rosenberg certainly did (we discussed the obvious problems with appropriation and the Roseland Ballroom in our 1935 essay, and go into even more depth in the Geek Out version.) […]

[…] This clip is pretty neat. First off, look at how much swing-style Charleston they’re doing. If you had never seen Lindy Hop anywhere else except this clip, you’d probably think the Charleston was the basic. There is one swing out, near the very end, and it’s a pretty snappy one, it doesn’t mess around. Notice there are hardly any basic turns, but there is a “tango” style move. A lot of these dancers most likely learned a lot by going to the Savoy, which dancers like White Roseland finalist Harry Rosenberg certainly did. (We discussed the obvious problems with appropriation and the Roseland Ballroom in our 1935 essay, and go into even more depth in the Geek Out version.) […]

[…] swungover.wordpress…. […]