Venmo: @bobbyswungover

This is the shorter, snack-sized version of this article. For the longer, Geek-Out version, click here. This is part of the Harvest Moon Ball essay series. To see all the Harvest Moon Ball essays, please visit Swungover’s HMB page.

The “New” Kid

On Aug 12, 1937, the Daily News announced the third Harvest Moon Ball. This is the year Lindy Hop — as a name, at least — turned ten years old.

Most of this article will focus on the Lindy Hop of the 1937 Harvest Moon Ball. However, we want to first discuss something important that happened in this year’s ball. In that announcement mentioned above, a new dance appeared in the listing of the divisions: “Collegiate Shag.” Those who read our 1936 HMB article will remember a Collegiate Shag couple had actually made it into the Lindy Hop finals, only to find themselves surrounded by Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers. (No pressure.)

Well, this next year, according to the Daily News, the “Collegiate Shag” was demanded by hundreds of the newly crazed, mostly-student dancers.

Everyone knows Lindy Hop was a product of the Black American culture of Jazz-era Harlem, New York. But what about this newcomer to New York, Shag? Where did it come from? And what are its cultural roots? Before we get the help of some Shag experts to help answer that, try this thought exercise: Imagine for a moment we simply said “You might not know this, but Shag was a ‘White dance.’” How would that make you feel about the dance? What would that mean to you? Would it make you feel uneasy, or perhaps the opposite — more comfortable with its existence? (For instance, a White Shag dancer being convinced it’s a “White dance” might feel comfort in knowing they perhaps don’t have to worry about navigating appropriation as much as a Lindy Hopper might.)

Now, imagine we said, “You might not know this, but Shag was originally a ‘Black dance.’” Now, how would that make you feel, and what would that mean to you? Did you all of a sudden find Shag “cooler” after that sentence, if you didn’t think it was cool before? Did it make you uncomfortable, knowing there was perhaps more of the problem of appropriation to consider than you had already thought?

And how did you feel about the dichotomy those questions imply — that “White swing dance” and “Black swing dance” are two valid categories in terms of looking at this specific situation?

We’d like to argue that thinking of jazz era partnership dances as “White dances” verses “Black dances” is not a very realistic, or useful, way to view them. First off, we will do so by arguing there’s no such thing as a jazz era dance (at least the ones the modern swing scene does) that doesn’t in some way share ownership with Black American artistic values.

Let’s begin with the music. “Collegiate Shag” as this dance is done today was evolved to jazz and swing music in the jazz era. What are some of the values emphasized in Black American Jazz music? Swung rhythm, improvisation, call and response, individuality interconnected with teamwork, sharing and collaboration between musicians and dancers, and sharing and shining among fellow musicians (such as found in solo trading, cutting contests, and jams). Now then, if a dance done to this music embodies and emphasizes those Black American artistic values, then those values are in its DNA. Even if White people predominantly developed them, they were doing so because they correctly interpreted those Black values in the music. In this sense, any swing dance that emphasizes those same values is tied to Black American dancing values on a fundamental level. Does Shag embody these?

Yes, indeed. Shag commonly shows values that are often emphasized in Black American culture, and that were not commonly emphasized in early 1900s European-American dancing culture: constant improvisation, solo dancing expression even within partnership dances, full-bodied dancing (all body parts available for expression), breaking away (partnering without physical contact), emphasis on rhythmic complexity, sharing and shining the dance, and a showcasing of many different personalities within its movement — such as humorous, elegant, fierce, or eccentric movement.

(Please note, we’re not saying European-American partner dancing is completely devoid of all of those traits, just that they are just not as emphasized, or in the same characteristic ways.) So, again, even if it were developed by White Americans from its very beginning, it still has all the hallmarks of a strong influence from Black American dancing and music values. (We would make a similar argument for there being Black American cultural values inherent in the Southern California dances, Balboa and “swing.”)

Okay, but, what about this “Collegiate Shag” the Harvest Moon Ball is showcasing — what are it’s literal origins? Where did it come from? Shag historians have differing points of view. Some think it most likely comes from vaudeville steps which have Black origins, others think it evolves from a dance named “Shag” commonly mentioned in papers from the Carolinas, which also probably had some roots in Black American dance forms and movement paired together with White American dances. (Whenever dancing from the South is concerned, there’s a pretty good bet Black American values are a part of it, as Black culture has always greatly influenced Southern culture. We will see this happen even more definitively by the creation of the Big Apple later this very year, 1937.)

As far as the Harvest Moon Balls go, its professed “expert” on Lindy Hop and Collegiate Shag was a man named Bernie Sager. Bernie was a very well-known and influential dance instructor at the time. And he had demonstrated the “Collegiate Shag” for the “dancing masters annual convention” in August of 1937, as “the very latest step in ball room fox trot dancing.”

Regardless of its mysterious and most-likely-complex origins, the Collegiate Shag swept the ballrooms of New York. Being done by mostly White youth and college students, the Shag dancers even overtook and overcrowded the Savoy ballroom during the rage, according to Norma Miller (as told in a personal interview).

Meanwhile, at the Savoy…

A few weeks before the prelims, (and only a couple weeks after a major heat wave), Herbert Whitey had a large group of his dancers practicing for three hours a day on the roof of the Savoy. At least, according to this article. (We wouldn’t be surprised if they practiced three hours a day, but the roof was probably a publicity stunt.) But, they were there for a cool picture, at least:

It’s hard to make out familiar faces, and almost all of the women dancers have their backs to the camera. But that is Whitey there on the right, looking over his dancers like a conductor. And it looks like the closest dancer to him could be Billy Ricker. And it’s probably John “Tiny” Bunch back in the back raising his arm. And possibly a young Al Minns in the white shirt to his right. Whitey at one point would reportedly have around 40 couples of dancers in his group — so it’s understandable if there are a lot of faces we don’t recognize. Those standing in the line in the back appear like middle-aged adults and look like an audience rather than dancers; they could be some of the parents there for the photo shoot, or staff at the Savoy.

Here in this picture are a skinny male dancer holding hands with a larger-framed female dancer. This is the first instance we personally have seen of a larger-framed woman dancer in Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers. It’s sad her dancing is not obviously on film that we know of, as she could be a real inspiration to dancers of the modern scene, who appreciate seeing all human body types reflected in the pioneers of the dance.

The Prelims

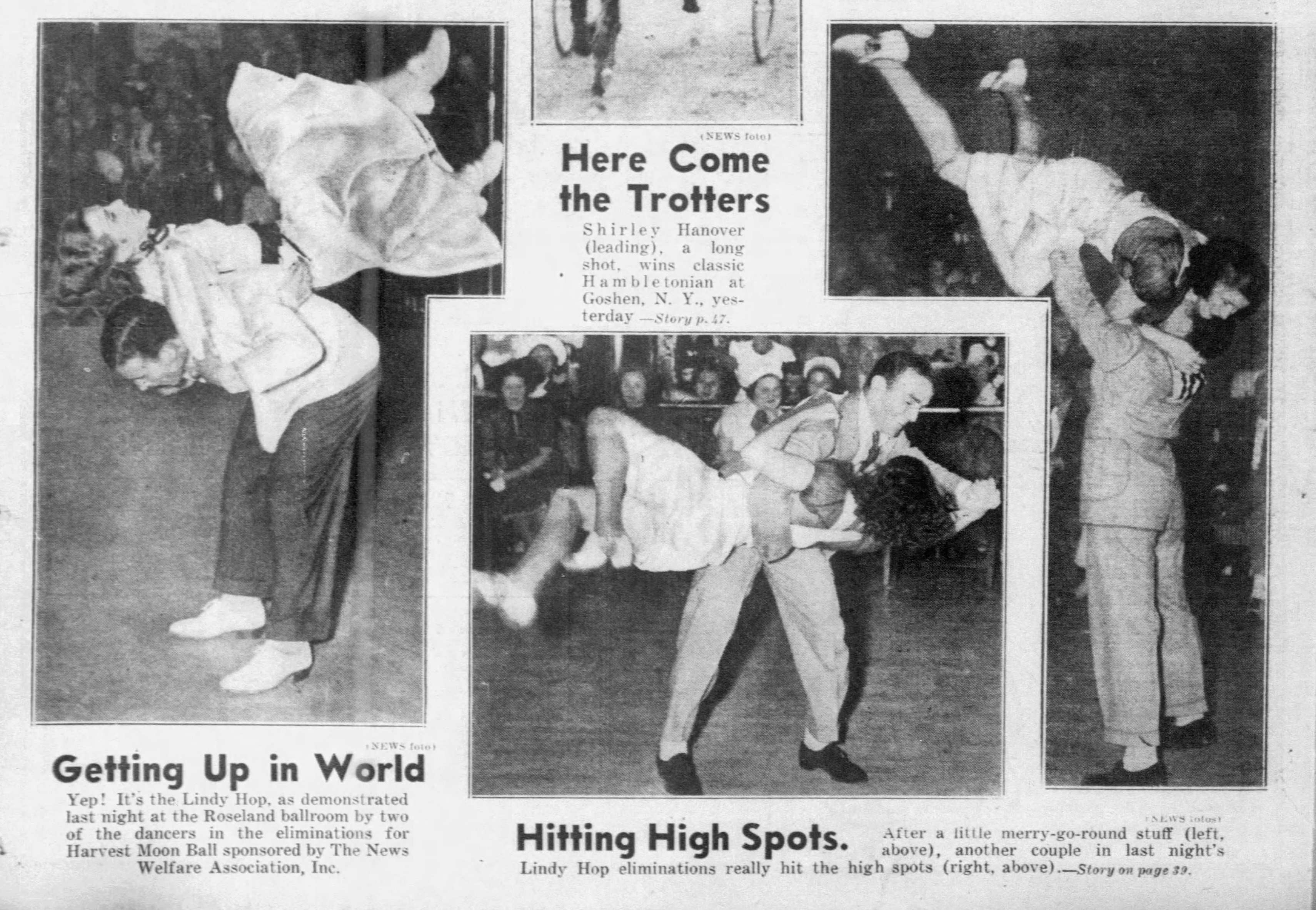

On August 12th, Roseland held their Lindy finals. The pictures from the Roseland prelims show that powerful acrobatics seem to have officially become widespread across New York’s Lindy Hop community.

The next night, at the Savoy, Willie Bryant — fantastic bandleader, co-inventor of the Shim Sham, and the honorary “Mayor of Harlem” — provided the music for the Lindy prelims. Though the college student Shag dancers had begun overrunning the Savoy ballroom around this time, there was no Collegiate Shag prelim at the Savoy, and no mention of why not.

The finalists at the Savoy included a lot of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers (or future Whitey’s). Gladys Crowder & Eddie “Shorty” Davis, Joyce James & Joe Daniels, Hilda Morris & Billy Ricker, Ann Johnson & Johnny Smalls, Wilda Crawford & Ernest Harris, Eunice Callen & Lefty Brown, Sarah Ward & William Downes, and Hazel Davis & William Ward. In fact, it’s possible all of the finalists were in his group.

The finalists at the Savoy included a lot of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers (or future Whitey’s). Gladys Crowder & Eddie “Shorty” Davis, Joyce James & Joe Daniels, Hilda Morris & Billy Ricker, Ann Johnson & Johnny Smalls, Wilda Crawford & Ernest Harris, Eunice Callen & Lefty Brown, Sarah Ward & William Downes, and Hazel Davis & William Ward. In fact, it’s possible all of the finalists were in his group.

Note the name Eunice Callen. In the fall of 1936, Eunice was 14 when she bet a friend of hers 50 cents that she could make it into the Lindy Hop finals of the Harvest Moon Ball — despite not knowing Lindy Hop. She walked into the former-laundromat-turned-club-house Whitey had rented for his Lindy Hoppers and told them her plan. Whitey had some of his dancers swing her out, and put her to training. Eunice, like many other dancers — Al Minns and Norma Miller, for instance — had learned on the Harlem street corners where children would dance for change. As she told Robert Crease in interviews he conducted for the New York Swing Society, she found training easy, except for the air steps, which Whitey demanded be done precisely. He’d fine them if they didn’t do it in the exact counts he asked for. As you can see, she made it to the finals. She collected her 50 cents.

In the picture below, it’s likely the woman in the right side couple is Eunice Callen with her partner Lefty Brown.

Whereas the Roseland Ballroom was only able to take three couples to finals this year, the Savoy got to take eight.

Interestingly, the article mentioned that “pecking” was introduced at this Prelim dance event, and that it had been developed by the Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers group that had been on tour and in A Day at the Races. Whitey seemed to be continuing to make a name for his group through the introduction of new dance steps, as we saw with the Suzy-Q in fall of 1936.

The Finals

On Aug 25th, the sold-out finals of the ball filled Madison Square Garden with 22,000 people. Once again, thousands not able to get a ticket crowded outside.

The evening wasn’t just all dance contests. Between the finals were performances by comedian Milton Bearle, the tap dancing of Bill “Bonjangles” Robinson, Cappy Barra’s all harmonica band, dance comedians Moore and Revel, and Phil Spitalny’s “All Girl” Band, to name just a few.

Lucky Millinder would be the music for the Collegiate Shag, Lindy Hop, and Tango.

Here’s the first, and not the last, time that we get to thank modern dancer and historian Sonny Watson for his research and sharing his research with the community. He has collected Harvest Moon Ball programs for years and published the numbers on his website Street Swing for the years he has programs for. We also luckily stumbled upon a 1937 program on Ebay. They were kind enough to print pictures of the program:

(According to an inflation calculator, 75 cents, the price of this admission, was roughly $14 in today’s money. We couldn’t imagine anything at Madison Square Garden costing that little today.)

With that in mind, let’s look at one of the several available 1937 Harvest Moon Ball Newsreels:

And here is our breakdown from compiling all of them and identifying the dancers we could:

Heat A

According to the dancer’s list, Heat A would be the third heat of the contest, the first one to introduce the Black Harlem dancers. All four couples seem to have been Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers based on their group dancing and our knowledge of them.

Gladys & Eddie

Gladys and Eddie here perform the first true Air Step we see in the Harvest Moon Ball. Fitting then, that it is none other than Over the back, the air step Frankie Manning describes inventing with Freida Washington in that fateful contest he has famously described that would introduce flips and throws into Lindy Hop. According to Frankie, that contest happened in late 1935 or early 1936. If it did occur then, then Air Steps were taking a little while to catch on to the other dancers, as this is a year and a half later, and neither the 1936 HMB or A Day at the Races showcased much more than a few Ace in the Holes (commonly called “Candlestick” today) and a Side Flip.

Here Gladys and Eddie (in the upper corner) perform their signature step, where Eddie turns and flips under Gladys’s arm:

(You might recognize that move as done by Ria DeBiase and Nick WIlliams in one of the most famous modern clips, the ULHS 2006 Liberation division.)

Something that was a strong tradition among the Savoy Lindy Hoppers that has hardly been worked with today in the modern era, is the idea of “comedy teams,” as Frankie calls them in his book. These are dancing couples that either enjoy adding lots of humor to their steps, or are dramatically different in size and/or shape to create an eccentric partnership. “Big” Bea and “Shorty” Snowden are the most famous example of this, and this next generation of Savoy dancers carried on the tradition.

In this very heat are two examples of “comical couples:” Gladys Crowder and Eddie “Shorty” Davis, and their inverse, the tall Johnny Smalls and smaller Anne Johnson. (We don’t know if “Smalls” was his legal last name or an ironic nickname. As we will see throughout HMB history, there were often obvious nicknames given in their registrations.)

Here, Eddie and Gladys create an unexpected “comical” effect by having the short dancer throw around the tall partner. So far we’ve only shown their tricks. But Eddie and Gladys also have some mean swing outs and other steps. Make sure to go and watch for their non-trick dancing — it’s beautiful.

Ann & Johnny

Here, for the first time on film, is Ann Johnson, that great daredevil follower who would famously fly through the air in Hellzapoppin with her partner, Frankie Manning. Those who have seen the 1935 and 1936 footage know that the Harvest Moon Ball newsreel makers love anything where followers are holding on and swinging their legs. So much that sometimes they’ll replay that same move from different angles, giving the mistaken impression that’s all a couple has done in their entire time on stage. Ann and Johnny are this year’s victims to this editing bias. But, for the record, it does look great.

Joyce & Joe

Joyce James is personally one of our all-time favorite jazz dancers of all time. Her nickname in the group was “Little Stupe,” and Joe Daniels, her partner and later her husband, was nicknamed “Big Stupe.” This was because they were not the best at replicating steps quickly, and didn’t realize it — but don’t worry, according to Frankie Manning, the names were affectionate. Here they are during a breakaway moment:

Hilda & Billy

Hilda Morris and Frankie Manning were partnered together by Whitey in 1934, and they won an Apollo Lindy Hop contest which resulted in a week-long gig, and a short tour that ended with the producers skipping town with all the money. It was one of the first Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers gigs and tours.

We don’t see much of Hilda Morris and Billy Ricker in this heat, but what we do see is the first instance of “Skate” Charleston we know of on film (and our wife’s favorite Skates):

Side note: Billy Ricker has a warm smile and demeanor in everything we have ever seen him in.

The Ensemble

Once again, a heat full of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers decided to go into ensemble dancing during their heat. This choreography was perhaps one of the ending numbers of the Whitey’s routine stage shows to come about after the introduction of ensemble dancing via the original “Stops” routine about a year or two earlier (according to Frankie).

Heat B

From the numbers listing, this was the last heat of the Lindy Hop contest. Heat B is not only short, we were not able to get any obvious number identifications from it. But we have some good guesses. (See the Geek Out Edition for those breakdowns).

Eunice & Lefty

Eunice Callem remembered dancing the 1937 Harvest Moon Ball with Walter “Count” Johnson (whom we will start to see quite a lot of in future Harvest Moon Balls). From this very brief visual of them, it looks like it could be Walter Johnson by his body type, but the dancing does not tell us enough. We went with the name the contest listed.

Recalling this night, Eunice said she had forgotten to test the floor before the finals, only to find it too slippery for her, and she felt she couldn’t be precise in her footwork. Furthermore, two buttons popped off of her costume during the heat, which lead to marks off of her score.

(Likely) Hazel & William

For the few seconds we get to see them dance, we’re obviously looking at a highly skilled, energetic, dynamic couple. We could watch that tuck-turn into a barrel-roll all day. By the way, this barrel roll turn is more linear than the 1936 HMB barrel turns — we’ll discuss the increased linearization of Lindy in future essays.

Heats C & D

Heat C

Here, for the first time we have seen in the Harvest Moon Ball, is a White couple that seems to be overly characterizing the Lindy Hop as a “goofy” dance. You can see them in every clip from this heat making exaggerated broken-away gestures towards each other. In the Harvest Moon Balls before this, the obviously White dancers have danced in ways similar to the majority of other White couples in this heat: Lots of emphasis on Charleston figures, and what looks like a desire to capture the Savoy stylings and footwork — just a desire not to move their bodies much, especially the hips and above, when they did it. They had not, up to this point, tried to obviously copy the more energetic and often-humorous spirit of Harlem Lindy Hop as performed by the Black dancers. But now a couple has started to, we’d argue, mis-read and oversimplify that spirit, and base their own dancing on that reading. We will discuss this further in future essays, as more and more White dancers begin to obviously interpret what the humorous aspect of Harlem Lindy Hop means to them.

Heat D

Finally, in the few seconds shown of heat D, we see that one trick step — where the leader puts the follower on the hip and the follower kicks — is being done by two couples.

1937 Lindy Hop

Air steps and more acrobatic steps have officially been introduced into the Lindy Hop by this time, but other than the over-the-back, they are still most often energetic sits and lifts and drags — there are not yet flips or vaulting air steps being done in the HMB. The one exception is Eddie Davis’s under-arm flip move. Also White dancers are now obviously doing dramatic trick steps.

The dresses hem-lengths of the era have been creeping up, and you might have noticed the dancing getting even more acrobatic. Joyce James smartly wore a slit skirt, which allows her a lot more freedom of movement that she takes full advantage of.

As we are not experts on Shag, we do not feel comfortable in discussing the shag dancing in the heats. We look forward to hearing what shag experts might say about them in their own discussions. All of our identifications in Shag were gotten from matching the numbers to their names in the program listings.

Winners

The shag winners were announced before the Lindy Hop: Ruth Scheim & John Englert, 1st. Joan & Gene Biggins, 2nd. And Virginia Hart & William Ledger, 3rd.

The winners of the Lindy Hop were:

Gladys Crowder & Eddie “Shorty” Davis.

In second, Joyce James & Joe Daniels.

And then, something exciting happened for the first time at the Harvest Moon Ball. They had to have a dance off for third place. And out of that dance off, Wilda Crawford & Ernest Harris took 3rd, and Hilda Morris & Billy Ricker took 4th.

Finally, Whitey had seen his dancers take all three places in the contest, which must have felt like a vindicating accomplishment. They even technically took all four of them. It was a good year for him and the Whitey’s in general.

Most, if not all, of the Savoy dancers in this contest might have been new to you. With the exception of Norma’s partner and close friend Billy Ricker, Frankie and Norma only occasionally mention some of these dancers in their books and even then don’t say much about them. This is most likely for a few reasons — They were veterans in Whitey’s group by this time, and the older groups might not have been around the younger groups as often as we might expect. And, the Whitey’s by this time was a pretty big group of dancers, as showcased in the practice picture above — that’s a lot of new faces to get to know. Furthermore, Norma and Frankie were doing so much touring and gigs by this time, they basically might not have had much of a chance to get to know most of these dancers intimately.

For the record, the final judges for the contests were, once again, five White men noted as Ballroom dancing experts, like Arthur Murray and Bernie Sager.

The Next Day

The Lindy Hop, as championed by the Black dancers of Harlem, and the new Collegiate Shag, as championed by mostly White youth, were the undeniable hits of the Ball and the newsreels.

Here are pictures shown in the Daily News following the 1937 ball.

The Aftermath

A week later, The Pittsburgh Courier, a Black American newspaper of the time, had this to say about the event.

This little column hints at a lot: Clearly other Black communities knew of and cared about the Harlem dancers performing in the large New York contest if this article was showing up in their local paper. There is also, understandably, a tone of pride for the Harlem dancers — and Harlem dance in general — being the obvious stars of the evening, and bringing a Black American flavor to the other dance forms. They even take a moment to enjoy the fact that Harlem Lindy Hoppers had appeared in A Day at the Races, which was seen in theaters throughout the country.

By the way, this same paper prints another interesting article a week later. It’s an article trying to explain this new popular dance called the “Big Apple.” That’s such an important and key story to the history of swing dance that we’re going to discuss that, and it’s interesting links to the 1937 HMB, in a separate post.

In September of 1937, a group of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers performed in the film Manhattan Merry-Go-Round. In a dance number with Cab Calloway, it looks like recent champs Gladys Crowder and Eddie “Shorty” Davis are seen in very short snippets with their fellow Whitey’s.

Then, in December, Whitey’s would go back to Hollywood to film a new dance sequence in Radio City Revels. The clip begins with Lucille Middleton and Frankie Manning swinging out first, before it cuts to 1937 champ Eddie “Shorty” Davis dancing with a new partner, Mildred Pollard.

Mildred Pollard is a name to keep an eye on —you might even have noticed that in the Radio City Revels clip, rather than being thrown around by her leader, she instead picks up Eddie.

In the next year, she will begin preparing for 1938’s Harvest Moon Ball with a young, lightweight new Lindy Hopper leader, and together they will capitalize on Mildred’s strength.

That young dancer’s name was Albert Minns.

Venmo: @bobbyswungover

Additional Notes:

- For an article on something else that was happening at the time, check out this article on the Hopping Maniacs at the Savoy in 1937.

Sources & Thanks

- HUGE THANKS to Ryan Martin, Forrest Outman, and Judy Pritchett for sharing their time, resources, expertise, and insight with me in working on this piece.

- Except where otherwise stated, all newspaper articles, pictures, and information on the details of the 1937 Harvest Moon Ball were taken from editions of the New York Daily News.

- Thanks so much to Robert Crease, Cynthia Millman, and The Frankie Manning Foundation for republishing the fantastic Robert Crease bios which are a great wealth to the history of the dance.

- When not otherwise stated, all other information, especially regarding the opinions and experiences of the original dancers, is from Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop by Frankie Manning and Cynthia Millman and Swinging at the Savoy: The Memoir of a Jazz Dancer by Norma Miller and Evette Jensen.

- Huge thanks to Jessica Miltenberger for her help in reviewing and editing the piece.

11 responses to “The 1937 Harvest Moon Ball”

[…] This is the longer, Geek-Out version of this article which may have more information and research than you may care about. For the shorter, Snack-sized version, click here. […]

[…] 1937. Just a couple weeks after the 3rd annual Harvest Moon Ball in August, the Black American newspaper The Pittsburgh Courier published an article trying to explain a new […]

[…] This is part of the Harvest Moon Ball essay series. Read more about the history of this defining event here: 1935, 1936, 1937 […]

[…] This is part of the Harvest Moon Ball essay series. Read more about the history of this defining event here: 1935, 1936, 1937 […]

[…] This is part of a series of essays that follows the rough time line of Savoy Lindy Hop from 1935 onwards. You may find the Harvest Moon Ball series interesting to go deeper into the grand time line of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers at this time: 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938. […]

[…] version, click here. This is part of the Harvest Moon Ball essay series. Read 1935 here, 1936 here, 1937 here, and the 1938 […]

[…] Out version here. This is part of the Harvest Moon Ball essay series. Read 1935 here, 1936 here, 1937 here, and the 1938 […]

[…] click here. Also, this is part of the Harvest Moon Ball essay series. Read 1935 here, 1936 here, 1937 here, 1938 here, and 1939 […]

[…] click here. Also, this is part of the Harvest Moon Ball essay series. Read 1935 here, 1936 here, 1937 here, 1938 here, and 1939 […]

[…] our 1937 essay we discussed the rise of Collegiate Shag’s popularity in New York, and the introduction of […]

[…] Lindy Hop with partnerships like “Dot” Moses & “Tiny” Bunch, Gladys Crowder & Eddie “Shorty” Davis, Mildred Pollard & Al Minns, and Tiny Anne & Tony […]